Por: Natalia Albin | @_nataliaalbin

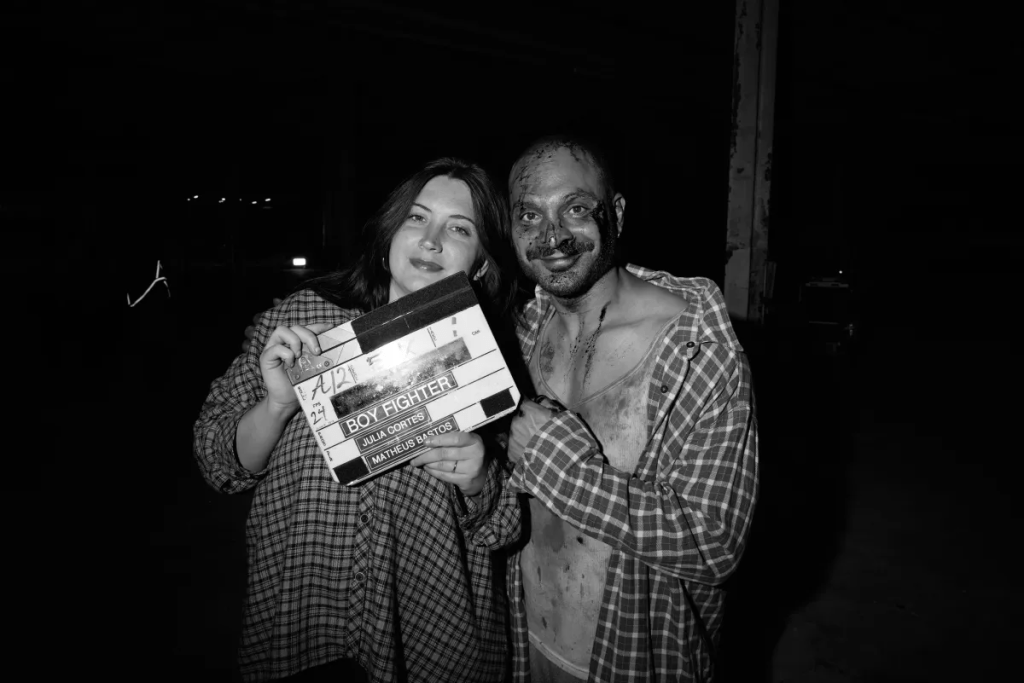

Apenas entro a la ceremonia de premiación de HollyShorts en Londres cuando me presentan a una cineasta que “tengo que conocer”. Se llama Julia Weisberg Cortés, y, para su sorpresa, me lanzo a saludarla con un abrazo. Tal vez es porque ya vi su corto que está en selección en HollyShorts, BOYFIGHTER, y es de esos que se sienten tan profundamente personales que dan la sensación de que ya conoces a la cineasta, como si tuvieras una conexión inexplicable. Y, ¿no es eso lo que hace la buena escritura?

A su lado está Alessandro Farrattini, quien se presenta con una sonrisa. Más tarde me entero que será el productor de su primer largometraje, The Coveted. Porque Julia Weisberg Cortés está ocupada. Está en Londres en parte para promocionar BOYFIGHTER, pero también se está preparando para rodar su largometraje en Escocia, además de tener dos series de televisión avanzadas y en desarrollo.

Con base entre Ciudad de México y Los Ángeles, Weisberg Cortés es escritora y directora, pero sobre todo es cuentacuentos, porque “así crecí y así he sido siempre”, me dice a la mañana siguiente, cuando nos sentamos para esta entrevista. Es la primera mujer de su familia en cursar estudios superiores en un campo creativo, y las historias que escuchó al crecer como mexicoamericana están en el ADN de cada una de sus películas.

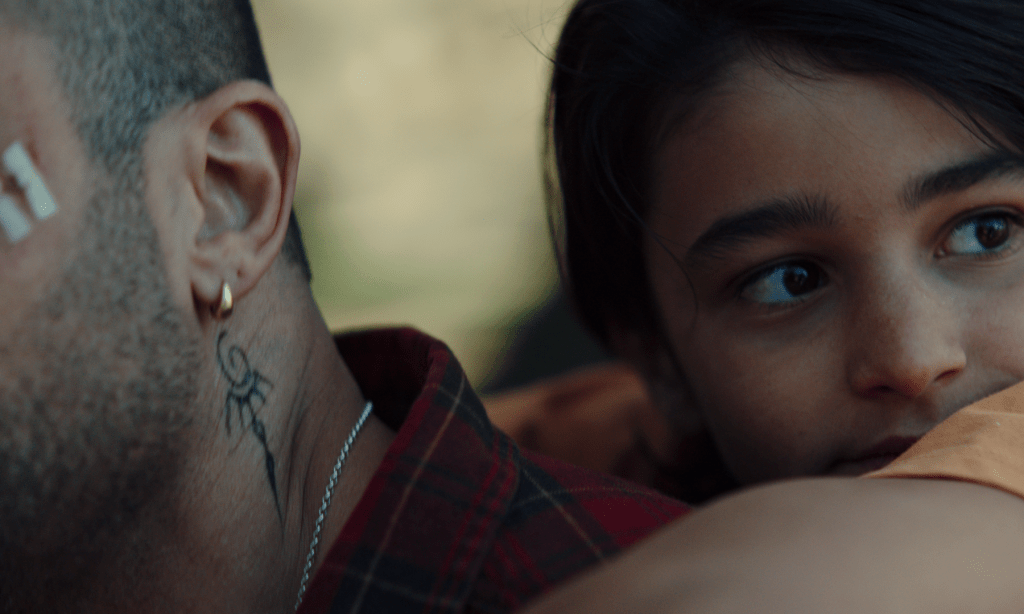

BOYFIGHTER no es la excepción. La historia, que sigue a un hombre que se prepara para enfrentarse a una tragedia, intercalado con recuerdos de su vida como luchador callejero y como padre, es a la vez visceral y meditativa, y nace de la pérdida de su hermano en 2023. “Fue una película que quise hacer para Richie, mi hermano, para honrar su lucha y también la gran fuerza de su espíritu y el amor que irradiaba,” es una de las primeras cosas que me dice.

En su último día en Londres, después de reuniones, promociones, entrevistas y preparación, Julia no finge no estar cansada, pero en cuanto empezamos a hablar de cine y de historias, su entusiasmo y su generosidad se desbordan.

Girls at Films: Sé que Boyfighter es una historia muy personal para ti. ¿Puedes hablarnos de tu inspiración y de por qué decidiste hacerla? No tienes que hablar de tu hermano, pero si quieres me encantaría escucharlo.

Julia Weisberg Cortés: Claro, no tengo ningún problema en mencionar a mi hermano, porque siempre digo que si vas a hacer una película como BOYFIGHTER, tienes que estar dispuesta a hablar de dónde viene. Perdí a mi hermano en 2023 por los mismos ciclos que han afectado, específicamente, a los hombres de mi familia durante generaciones. Perdimos a mi abuelo, a mi bisabuelo, a mi tío (a quien nunca conocí), el único hermano de mi mamá, y a muchos de mis primos; todos murieron por la misma… guerra violenta, supongo que podría llamarse así. Gran parte de eso viene de la falta de acceso, de la falta de oportunidades. Y aunque obviamente querían que sus hijos tuvieran una vida diferente, hay momentos en los que, cuando naces en cierto lugar, simplemente te quedas atrapado, ¿sabes? Quería hacer una película que no tuviera miedo de mirar de frente ese tipo de historia trágica.

Creo que BOYFIGHTER no teme mirar directamente a la tragedia, pero no diría que es una película sin esperanza. Al final, lo que busca es iluminar la idea de que dentro de la tragedia también hay un amor inmenso. La presencia del duelo es la presencia del amor.

GAF: Qué respuesta tan bonita. Creo que eso se refleja mucho en algo que hiciste en el montaje, y asumo que ya venía desde el guion. La película no es lineal, así que no hay un solo bloque dedicado únicamente al duelo. Hay momentos de amor intercalados entre el dolor. Escucharte hablar sobre eso tiene sentido. ¿Cómo decidiste dónde colocar esos momentos para respirar? Esos instantes en los que sabemos que algo terrible ha ocurrido, vemos a tu personaje principal en ese lugar emocional, y luego nos permites tomar aire regalándonos imágenes de amor preciosas.

JWC: Soy mucho más exploratoria durante la preproducción y el rodaje, y en cuanto llegamos a la postproducción, ya sé muy bien qué va a funcionar y qué no. Fue muy claro, desde muy temprano en el rodaje, que esta iba a ser una película que se construiría en la sala de edición y que sería muy experimental en su estructura.

Más allá de eso, quería que la película se pareciera mucho a la memoria, que se sintiera como se sienten los recuerdos. No solo a nivel visual, sino también en el diseño sonoro, para mí era fundamental incorporarlo. Por ejemplo, la escena final está acompañada por los sonidos del lago en Louisiana. Y eso apunta justo a lo que mencionabas, que en medio de una gran tragedia también existe el recuerdo. Como pasamos toda la película estableciendo que esos sonidos están conectados con su hijo y con su hijo en el agua, espero que la gente pueda entender que se trata de una conexión de amor con su hijo.

GAF: ¿Hay algo sobre el duelo, sobre tu propio duelo, que aprendiste haciendo este corto?

JWC: No es necesariamente una gran epifanía ni nada, pero creo que cuando escuchas sobre el duelo, piensas… va a llegar. Todos pasan por eso, ¿sabes? Es parte de la vida. Pero luego te toca la experiencia, y te das cuenta de lo mucho que altera tu vida. El pensamiento de perder a alguien que amas más que todo, es sofocante, y eso es sólo el pensamiento. Luego pasa, y escuchas estas cosas como, “bueno, se va a volver más fácil.” Y no creo que sea el caso. Creo que siempre va a ser así de difícil, siempre vas a tener una parte de ti que ya no está, y creo que es importante decirlo.

Lo que amo sobre BOYFIGHTER es que dice que está bien mirar eso directamente y nos deja explorar ese momento de duelo sin necesariamente asignarle un propósito. Lo que me enseñó es que está bien tener un duelo profundo, sabiendo que el poder de tu duelo sólo es tan grande como el poder de tu amor. Entonces BOYFIGHTER fue una gran película para mi para sostener el espacio para la profundidad de mi dolor, pero también la profundidad de mi amor.

GAF: Hay un diálogo que se me quedó de la película, “cuando creció nos dimos cuenta que no nos caíamos muy bien.” Y hay ese sentimiento en familias, un sentido de pérdida que experimentamos incluso antes de la muerte. Y no sé si estábas pensando en eso, que tal vez perdió a su hijo antes de perderlo físicamente, entonces hay momentos de pérdida durante la vida que no vienen sólo de la muerte.

JWC: Creo que al mirarlo específicamente a través del mundo de la pelea de los personajes, y, obviamente, del hecho de que él es un hombre que ha conocido la dureza, cuando estás en presencia de la violencia vas a tener una vida complicada y relaciones complejas y difíciles. Cuando mi hermano murió, yo estaba muy enojada con él y no estábamos en los mejores términos.

Así que, para mí, ese diálogo nace de ahí. Porque recuerdo que cuando mi hermano murió no quería ir, no quería ver su cuerpo y no quería enfrentar realmente lo que había pasado. Estaba muy enojada con él, porque sentía: “claro que te moriste, ¿Qué esperabas? Lo hemos visto una y otra vez en los hombres de nuestra familia”. Estaba tan enojada y tan llena de amargura. Y creo que, de alguna manera, eso es por lo que está pasando Diego. Empiezas a inventar todas estas excusas sobre por qué no quieres enfrentar ese momento y por qué ya no quieres estar presente para esa persona. Así que sí creo que es como una forma de duelo anticipado, pero aún más creo que es una negación, porque simplemente no quieres enfrentarte a la realidad de esa pérdida.

GAF: Empiezas y terminas la película con un mito; ¿cuánto crees que nuestros mitos y los mitos que nos contamos sobre el mundo moldean quiénes somos?

JWC: Todos vivimos en nuestras pequeñas ilusiones. Y nos contamos cosas para hacer la vida más maravillosa, más digerible, más pacífica, lo que sea. En realidad, todo son historias.

La idea del mito es muy normal para mí, porque vengo de una familia en la que eso es lo que hacemos. Me han contado tantas historias que quizá nunca ocurrieron realmente, pero son fundacionales, como la de mi abuela naciendo en un río, y cómo casi se morían de hambre, esta gran historia de cómo mi abuela llegó al mundo. Eso siempre se usó para hablarme sobre resiliencia. Así que, ahora al mirar atrás, tengo tantas pequeñas historias como esa que absolutamente moldearon quién soy y mi identidad. Y ahora que me he hecho mayor y me he dado cuenta de que probablemente sólo son historias, siguen siendo tan importantes, casi tan importantes como los hechos.

GaF: Siento que el mito es algo muy latinoamericano; ¿cuánto sientes que tu mexicanidad moldea tu forma de hacer cine?

JWC: 100%. Cuando originalmente me propuse hacer BOYFIGHTER, quería hacerla en México. En San Luis Potosí hay un lugar llamado La Huasteca. Quería filmar allí. Y quería que fuera mucho más como peleas a puño limpio, como lucha libre mexicana. Pero con el tiempo las películas crecen, y tuve que hacerla en Estados Unidos, y tuvimos que contratar a actores no mexicanos.

Creo que, en general, todo está arraigado en mi lado mexicano. Mi estilo de narración es muy similar al de mi abuela, mi abuelo y mi mamá. BOYFIGHTER fue mi primera película en inglés, lo cual también fue muy particular, porque la historia del hombre con huesos de piedra era una historia que siempre se contaba en mi casa, pero en español. Y fue muy interesante escucharla en inglés; se sentía muy ajena.

GaF: La forma en que escribes se siente como la de esos escritores que nunca podrían hacer otra cosa, tienes que escribir. ¿Desde cuándo sientes que escribes y cuentas historias? ¿Sientes que ha sido un trabajo o que ha sido desde siempre?

JWC: Ojalá, y no lo digo solo por decirlo, tuviera otra cosa que amara tanto como esto y en la que fuera buena. Porque es una profesión muy intensa y agotadora. Supongo que se podría decir que he sido escritora toda mi vida. No crecí rodeada de muchos libros, pero sí crecí con alguien, ya fuera mi mamá o mi abuela, contándome una historia cada noche. No siempre fui cineasta, no tenía acceso a una cámara, pero sí tenía acceso a la historia.

Y de hecho, cuando estaba haciendo scouting en México, di una entrevista a un periódico local en La Huasteca, y esta parte en particular de la zona sigue estando muy desconectada. Mucha gente no tiene internet ni interfaces digitales. Y me preguntaron: “si hubiera niños aquí que quisieran hacer lo que tú haces, ¿qué consejo les darías?”. Y obviamente no podía decir lo mismo que le diría a alguien en Los Ángeles, que es simplemente encontrar una cámara y hacer algo. Porque estos niños no tienen ese tipo de acceso, así que les dije: “si eres cineasta, eres un cuentista”. Las historias son lo que abren puertas y lo que nos conecta, y eso se puede hacer a través de la escritura. Y si no lees ni escribes, entonces tienes que volver al inicio mismo de las historias, que es completamente verbal y consiste en ser imaginativo y expresivo a través de las palabras.

Así fue como crecí y como siempre he sido. Pero he tenido la suerte de ser la primera persona, por parte de la familia de mi mamá, en poder perseguir una educación superior y un sueño. Así que ha sido increíble poder tomar algo que es tan central en el linaje de mi familia y convertirlo en mi profesión, aunque sea difícil.

GaF: Este no fue tu primer rodeo. Has hecho otros cortos, estás trabajando en una serie de televisión. ¿Cómo es tu proceso? ¿En qué se diferencia uno del otro?

JWC: Es bastante diferente entre la televisión y el cine. Con el cine soy mucho más emprendedora, supongo que se podría decir así. Conociste a Alessandro anoche, mi productor, y estamos intentando hacer un largometraje. Porque he tenido la suerte de que con cada película que hago consigo más dinero, actores más grandes. Y pienso… ahora voy a poner todo eso junto e intentar realmente hacer mi primer largometraje.

Sé que cuando escribo una serie de televisión, se la voy a entregar a alguien para que la lleve adelante y la haga, lo cual definitivamente afecta el tipo de historias que estoy dispuesta a explorar en televisión. Todo lo que escribo es personal, pero si voy a entregárselo a alguien, no va a ser como una película como BOYFIGHTER. O como mi largometraje, que es profundamente personal sobre mi infancia y la infancia de mi mamá.

GaF: Esto es una buena transición hacia lo que viene para ti, ¿puedes hablar de eso?

JWC: Tengo dos series de televisión. Una se llama The Golden Children y la otra se llama Moonshine. The Golden Children ha pasado un poco a segundo plano, porque Moonshine ya tiene productora. Pero The Golden Children fue lo que me abrió las puertas al mundo de la televisión. Trata sobre comunidades romaníes en Estados Unidos. Moonshine la estoy desarrollando con la empresa de Gina Prince-Bythewood, quien dirigió The Woman King, y trata sobre las mujeres que desaparecen en las montañas Apalaches en Estados Unidos. Estamos intentando que se sume una directora para dirigir el episodio piloto.

Y tengo mi largometraje aquí en el Reino Unido sobre dos hermanas gemelas; una de ellas nace con polio, por lo que tiene una discapacidad severa en la pierna, y la otra nace sin polio. Y trata sobre cómo esta discapacidad ha hecho que sus vidas sean tan diferentes. Vamos a filmarlo en Escocia, con suerte en agosto.

GAF: Estoy muy emocionada de entrevistarte sobre tus otros proyectos, es muy refrescante entrevistar a personas que son tan generosas con su tiempo y con sus respuestas. Así que muchas gracias.

JWC: Gracias a ti. Eso significa mucho. Sí, claro, te aviso cuando venga algo más y ojalá podamos volver a encontrarnos.

Natalia Albin

Es una escritora y emprendedora mexicana viviendo en Londres. Sus escritos generalmente examinan las conexiones entre justicia social, inmigración y feminismos con cine, arte y cultura.

ENGLISH VERSION

Julia Weisberg Cortés: “Within tragedy there’s also great love. You know, the presence of grief is the presence of love”

I’ve barely walked into the HollyShorts Awards Ceremony in London when I’m dragged to be introduced to a filmmaker I “have to meet”. Her name’s Julia Weisberg Cortés, and to her surprise, I rush to hug her hello. It’s perhaps because I’ve already seen her film in selection at HollyShorts, BOYFIGHTER, and it’s one of those that feel so deeply personal that you feel you already know the maker, like you have some connection. But isn’t that what good writing should make us feel?

Next to her is Alessandro Farrattini, who introduces himself with charming amusement. I later find out he’s to produce her debut feature film, The Coveted. Because Julia Weisberg Cortés is busy. She’s partly in London to promote BOYFIGHTER, but she’s also preparing to shoot her feature in Scotland, in addition to having two television shows close to and in development.

Based out of Mexico City and Los Angeles, Weisberg Cortés is a writer and director, but most of all she’s a storyteller, because “that’s how I grew up and how I’ve always been,” she tells me the next morning when we sit down for an interview. She’s the first woman in her family to pursue higher education in a creative field, and the stories she heard growing up as a Mexican American are threaded through every single one of her films.

BOYFIGHTER is no exception. The story, which follows a man preparing to confront tragedy interspersed with memories of his life as a street fighter and a father, is both visceral and meditative, comes from the loss of her brother in 2023. “It was a film that I wanted to make for Richie, my brother, to honor his struggle and also the great power of his spirit and the love that that he permeated,” is one of the first things she tells me.

On her last day in London, after meetings, promotions, interviews and prep, Julia doesn’t pretend to not be tired, but as soon as we start talking about filmmaking and stories, her excitement and generosity comes across in spades.

Girls at Films: I know that Boyfighter is a very personal story to you. Can you talk about your inspiration and why you did it? You don’t have to talk about your brother, but if you want to, I’d love to hear it.

Julia Weisberg Cortés: Of course, no issue mentioning my brother, because I always say if you’re going to make a film like Boyfighter, you have to be willing to talk about where it comes from. I lost my brother in 2023 to the same cycles that have plagued, specifically, the men in my family for generations. We lost my grandfather, my great grandfather, my uncle, who I never met, my mom’s only brother, many of my cousins all died from the same… violent war, I guess you could call it. A lot of which comes from, you know, lack of access, lack of opportunity. And even though they wanted their kids to know a different life, it’s just times when you’re born in a certain place you just, you get stuck, you know? And so I wanted to make a film that was unafraid to really look directly into that kind of tragic story.

I think that Boyfighter is not afraid to look directly at tragedy. But I wouldn’t say it’s a hopeless film. What it ultimately is meant to do is shine a light on the idea that within tragedy there’s also great love. The presence of grief is the presence of love.

GAF: That’s a really lovely answer. I think it’s reflected in something that you did with the edit, and I assume it came from the script. It’s non-linear, so you don’t have a whole chunk of just grief. You have chunks of love in between the grief. Hearing you say that now it makes a lot of sense. How did you choose where to have those breathing moments? Where you know something really bad has happened, and you get your main character in that space, and then you let us breathe by giving us the most stunning imagery of love.

JWC: I’m a lot more explorative in pre-production and production, and then as soon as post-production comes, I know what’s going to work and what’s not going to work. And it was very clear, very early into shooting that this was going to be a film that is going to be pieced together in post and be very experimental in its structure.

I think aside from that, though, I wanted the film to be very much like memory, to feel kind of like how memories do. Not just visually, but also with the sound design. It was really important for me to bring that in. For example, the very end scene is accompanied by the sounds of the well of Louisiana. And that’s meant to point towards what you were saying, where in this presence of great tragedy, there’s also this memory. Because we just spent the whole film establishing to the audience that these sounds are connected to his son and his son on the water, I hope that people are able to connect that it’s a love connection to his son.

GAF: Is there anything about grief, about your own grief, that you learned through making the film?

JWC: It’s not necessarily any kind of major epiphany or anything, but I think that when you hear about grief, you’re like… it’ll come. Everybody goes through it, you know? It is part of life. But then you actually experience it, and you kind of realize how truly life altering it is.

The thought of losing someone that you love more than anything, it’s suffocating, just the thought of it, right? But then when it actually happens, you get these lines like, “oh well, with time, it’ll get easier”. And I don’t think it will. I don’t think it will. I think that it will always be this hard, and you’ll always have a piece of you that’s gone, and I think that that’s important to say.

What I love about Boyfighter is that it says it’s okay to look directly at this and really lets us explore that moment of grief without necessarily assigning it some kind of end or bigger purpose. What it showed me is that it’s okay to grieve really deeply, just knowing that the power of your grief can only be matched by the power of your love. So Boyfighter was a really amazing film for me to hold space for the depth of my grief, but also the depth of my love.

GAF: There’s a line that stuck with me in the film, “when he grew up, we realized we didn’t like each other very much” — and there’s that sense in families, a sense of loss that we experience even before death. And I don’t know if you were thinking of that, that maybe he lost his son before physically losing him, and so there’s bits of grief throughout life that aren’t just with death.

JWC: I mean, I think that looking at it specifically through the lens of the characters’ world of fighting, and obviously that he’s a man that has known hardship. When you’re in the presence of violence, you’re going to have a complicated life, and you’re going to have complicated, tumultuous relationships. And, you know, my brother, when he passed, I was very upset with him, and we weren’t on the best terms.

And so for me, that line came from that. Because I remember when my brother died, I didn’t want to go and I didn’t want to see his body, and I didn’t want to really face what had happened. And I was very angry with him, because I felt like, “of course you fucking died. What were you expecting? We’ve seen it time and time again, and the men of our family”. I was so angry and so bitter. And I think that, in a way, that’s kind of what Diego is going through. And you come up with all these excuses as to why you don’t want to face that moment and why you don’t want to show up for that person anymore. So I do think it is like a form of pre-loss, but also even more so I think it’s a denial, because you just don’t want to face the reality of that loss.

GAF: You start and end the film with a myth, how much do you think that our myths and the myths that we tell ourselves about the world shape who we are?

JWC: We’re all living in our own little delusions. And we tell ourselves things to make life more wondrous, more digestible, more peaceful, whatever. It really is all storytelling.

The whole myth idea is very normal for me, because I just come from a family where that’s what we do. I’ve been told so many stories that maybe never actually happened, but they’re foundational, like my grandmother being born in a river, and how they were almost starving, this grand story of how my grandmother entered the world. That was always used to tell me about resilience. Looking back, I have so many little stories like that that absolutely shaped who I am and my identity. And now that I’ve gotten older and I’ve realized that they’re just probably just stories, they’re still so important, they’re almost as important as the facts.

GaF: I feel like that sort of foundation and myth is such a Latin American thing, how much do you feel like your Mexican-ness shapes your filmmaking?

JWC: 100%. When I originally set out to make Boyfighter, I wanted to make it in Mexico. In San Luis Potosí there’s a place called La Huasteca. I wanted to film there. And I wanted it to be a lot more like bare knuckle fighting, reminiscent of Mexican wrestling. But eventually films grow, and I had to make it in the US, and I had to use non-Mexican actors.

I think, though, ultimately it’s all rooted in my Mexican side. I think my style of storytelling is very similar to my grandmother’s and my grandfather’s and my mother’s. Boyfighter was my first film in English, which was also really unique, because the story about the man with stones as bones was a story that was always told in my house, but in Spanish. And it was so interesting hearing it in English, it felt very foreign.

GaF: The way that you write feels like you’re one of those writers that would never be able to do anything else, you have to write. You’re a storyteller. How long have you felt like you’ve been writing and telling stories? Do you feel like it’s been work or it’s been forever?

JWC: I wish, and I’m not just saying this, I had another thing that I loved as much as this, and that I was good at. Because it’s a very intense and exhausting profession. I guess you could say I’ve been a writer my whole life. I didn’t grow up with a bunch of books, but I did grow up with somebody, whether it was my mom or my grandmother, telling me a story every night. I wasn’t always a filmmaker, though, I didn’t have access to a camera, but I did have access to the story.

And actually, when I was scouting in Mexico, I interviewed with a local newspaper in La Huasteca, and this particular part of the area is still very off-grid. A lot of the people don’t have internet or digital interfaces. And they asked me, “if there were kids here that wanted to do what you do, what advice would you give them?” And obviously I couldn’t say what I would say to somebody in LA, which is just find a camera and make something. Because these kids don’t have that kind of access, and so I told them, “if you’re a filmmaker, you’re a storyteller”. Stories are what open doors and are what connect us, and that can be done through writing. And if you don’t read or write, then you have to go back to the very beginning of storytelling, which is all verbal and being imaginative and expressive through your words.

I’ve been fortunate enough to be the first person on my mom’s side of the family to be able to pursue a higher education and a dream. So it’s been really amazing to be able to take something that is definitely so central to my family lineage and make it my profession, even though it’s hard.

GaF: This was not your first rodeo. You’ve done other shorts, you’re working on a TV series. What does your process look like? How does it differ from one to the other?

JWC: It’s pretty different between TV and film. With film, I’m much more entrepreneurial. I guess you could say, you know. You met Alessandro last night, my producer, and we’re trying to make a feature film. Because I’ve been fortunate enough that with each film I’ve made, I get more money, bigger actors. And I’m like… let me now put all of that and really try to make that first feature film.

I know that when I’m writing a TV show, I’m going to hand it off to someone to go and get it made, which definitely affects the kind of stories that I’m willing to explore on television. Everything I write is personal, but if I’m going to give it away to someone, it’s not going to be like a film like Boyfighter. Or like my feature, which is deeply personal about my childhood and my mom’s childhood.

GaF: This is a nice segue into what’s next for you, can you talk about that?

JWC: So I have two TV shows. One is called The Golden Children, and one is called Moonshine. The Golden Children has taken a little bit of a backseat, because Moonshine has been picked up. But The Golden Children was the thing that broke me into the TV space. It’s about Romani compounds in the United States. Moonshine I’m developing with Gina Prince-Bythewood’s company, she directed The Woman King, and it’s about the women that go missing in the Appalachia mountains in the United States. We’re trying to get a director attached to direct the pilot episode.

And I have my feature here in the UK about twin sisters, one of them is born with polio, so she has a really debilitating leg disability, and the other was born without polio. And it’s about how this disability has made their lives so different. We’re filming that in Scotland, hopefully in August.

GAF: I’m looking forward to interviewing you about your other projects, it’s really refreshing to interview people that are so generous with their time and their answers. So thank you so much.

JWC: Oh, thank you. That means a lot. Yeah, no, of course, I’ll let you know when, when something else is coming and we can hopefully meet again.

Debe estar conectado para enviar un comentario.